STORY 1

Enjoy Artifacts and the Four Seasons

at the Nara Crafts Museum

Learn the origins of traditional crafts in Japan

In 710, the capital was transferred to Heijokyo–ancient Nara.

During the historical period known as the Nara Era, Japanese envoys were dispatched to Tang China while foreign delegations came to Japan from Asian countries such as Persia, India and China. They brought various cultural objects such as books, medicine, clothing and ornaments to the capital city of Nara, contributing greatly to Japan’s cultural development.

Craftwork brought into Nara was modified and refined with new creative ideas, which spread throughout Japan. These handicraft techniques were fused with local materials, and produced unique regional cultures. Nara is the point of origin for beautiful artifacts preserved and handed down to the present generation.

The Nara Crafts Museum presents handicraft techniques cultivated for over 1300 years, along with their evolution.

At the Nara Crafts Museum, sample the charms and lengthy traditions of Nara’s local crafts.

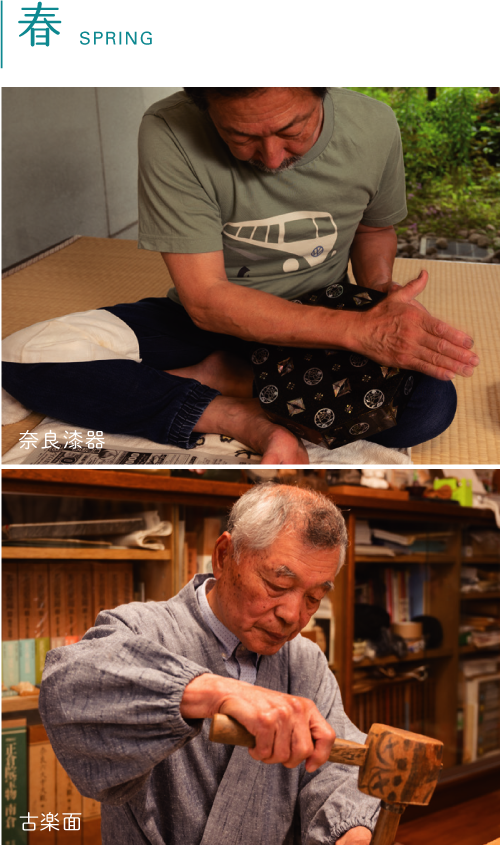

SPRING | February–April

The Omizutori Ceremony held at Todaiji Temple is a herald of spring.

Stately Nara Shikki (lacquerware) furniture and furnishings add elegance to the solemn rituals of the Omizutori Ceremony, a Buddhist ritual carried out by monks specially purified for the ceremony held at Todaiji Temple each March.

An exotic type of masked theater is said to have been performed at the first ceremony.

Kogaku Men is a term for masks patterned after these ancient face coverings. The masks are now highly regarded as interoir decorative items.

Nara Shikki

Items brought to Nara via the Silk Road in the Nara Era include many lacquerware works with mother-of-pearl or decorated via other methods such as gold or silver paint, and Nara is recognized as the birthplace of Japanese lacquerware. In Japan’s feudal era, nushiyaza artisans attached to temples and shrines lacquered buildings and created lacquerware works. Contemporary Nara Shikki features a technique known as raden, involving the inlaying of mother-of-pearl. By means of this technique, lustrous seashells such as marbled turban are inlaid on lacquerware containers and furniture as well as on accessories and cutlery such as chopsticks.

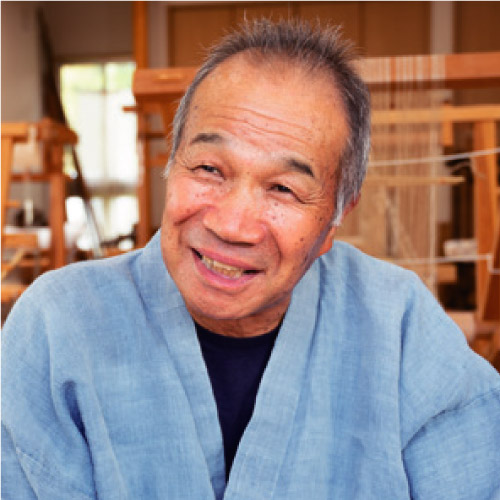

Yamamoto Satoshi

Yamamoto describes Nara Shikki as follows. “The process of making Nara Shikki involves more than simply applying lacquer on wood. It also involves painting layers of non-oily lacquer and then polishing it with special charcoal to bring out the luster. The process takes ten times as long as it does for ordinary lacquerware, resulting in high prices. However, this kind of lacquerware is surprisingly durable, and can be used casually.” He adds, “Both ice cream and beer are especially delicious when served in lacquerware containers.”

Kogaku Men

Kogaku Men are elaborate replicas of masks used in ancient, masked theater and court dance. These dances were introduced to Japan in the Asuka Era (592-710), when Buddhism was introduced to the country. Various types of masks have been used since the importation of the dances. Some of the masks used in the Nara Era (710-794) are preserved as the Shosoin treasures. Initially, the masks completely covered the actor’s head, with masks covering the face alone developing later. The latter type of mask went on to influence the development of those used in Noh and Kyogen plays. After World War II, these masks became popular as decorative ornaments. Replicas were created as artifacts, and sold at department stores all around Japan. In Nara, where numerous temples and shrines are located, court dances are still performed today for various occasions. For that reason there are many mask creators who produce not only replica masks for display but also wooden masks actually used in Noh and Kyogen plays.

Nakabo Ryudou

Nakabo has been creating masks for over 60 years. He says, “I do everything I can to make the masks as authentic as possible. For example, I go to museums to inspect masks actually used in ancient times, and study the details in books.” A number of masks are displayed in his workshop. Some of these makes were used in the masked theater performed at the ceremony to consecrate the Great Buddha statue. Also displayed there are masks used in “Ranryoo,” a court dance still performed in shrine and temple rituals. Nakabo also creates masks used in Noh and Kyogen plays.

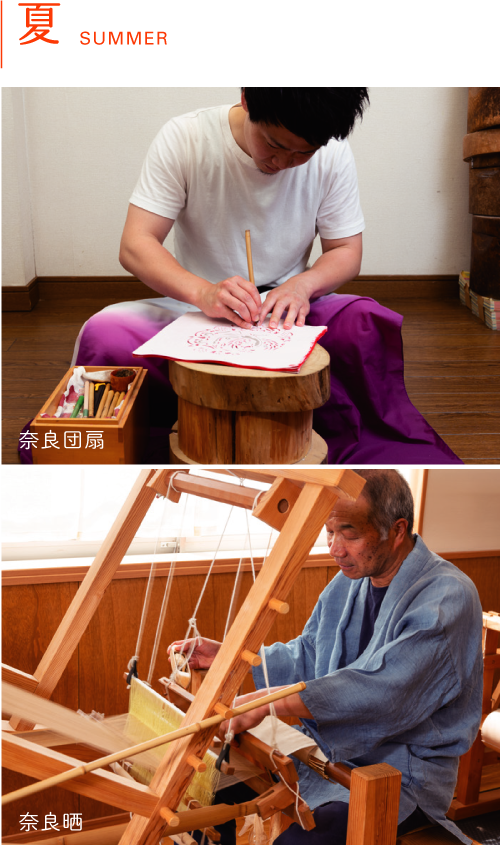

SUMMER | May–July

Summer in the Nara Basin is hot and humid.

The locals have devised various ways of keeping cool.

Nara Uchiwa fans feature watermarked patterns imprinted on Japanese traditional handmade paper.

The detailed craftmanship of these fans will astonish you.

The breeze produced by these fans is soft and pleasant. The fans are also an attractive accessory for yukata (cotton kimono for summer wear).

In exploring the Naramachi area, you’ll find shop curtains made of Nara Sarashi (special hemp cloth) at the entrance of traditional merchants’ houses.

Accompanied by the sound produced by cooling breezes upon wind chimes hung from eaves, these curtains evoke nostalgic Japanese scenery.

Nara Uchiwa

Nara Uchiwa fans feature delicate watermarked patterns imprinted on beautifully dyed Japanese traditional handmade paper. Typical motifs for these patterns include Tenpyo Monyo (ancient patterns often observed in the Shosoin treasures), deer, wisteria, and scenes from “Manyoshu” (an 8th century anthology of Japanese poetry), which are patterns symbolizing Nara. Nara Uchiwa are said to have been derived from Shibu Uchiwa fans, created in the Nara Era as piecework by priests at Kasuga Taisha Shrine. These fans were gradually refined, and perfected as Nara Uchiwa early in the Edo Era (1603-1868). Nara Uchiwa are not only beautiful but also highly practical. The practicality lies in the 60-90 frames on which the paper is pasted. Just a flick of the wrist is enough for these flexible fans to generate a pleasant breeze. Until the 1940s, Nara City had a number of Nara Uchiwa shops.

Ikeda Tadashi

Despite his youth, Ikeda is the 6th head of the Nara Uchiwa specialty shop, the only one continuing to specialize in Nara Uchiwa. Assisted by members of his family, Ikeda dyes paper and make frames in winter, then in spring and summer imprints watermarked patterns, completing the products.

Ikeda’s works are not limited to uchiwa fans with traditional patterns. With a serious expression on his face, he says, “I create original products every autumn. I’m working not only to preserve the tradition of Nara Uchiwa but also to hand down items of fresh appeal to the coming generations.”

Nara Sarashi

Nara Sarashi is special cloth made from hemp. Creators spend about one month carefully weaving hemp yarn then washing the cloth in clear water until it turns pure white. This hemp cloth has been used in clothes worn by monks or priests since olden times. A man named Kiyosumi Genshiro is credited with having improved the cloth-washing process in the Azuchi Momoyama Era (1573-1603), providing the impetus for textile manufacturing to flourish. Later, the weaving process too was improved, and the cloth became popular for use in formal samurai attire and in summer kimono. The cloth was supplied to the Tokugawa shogunate, and Tokugawa Ieyasu created a system for controlling the manufacture and sale of hemp. Today, Nara Sarashi is used to make napkins or pouches used in the tea ceremony. Daily goods such as coasters and drawstring bags are also popular.

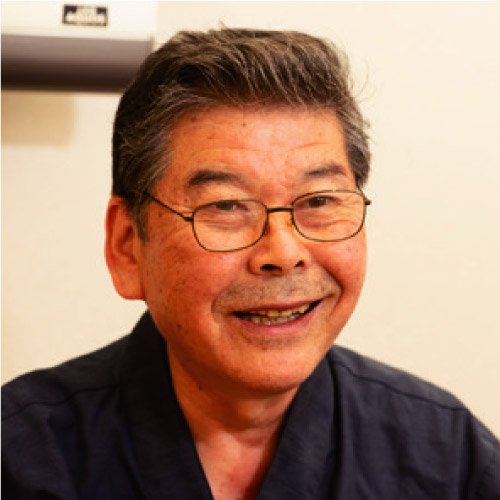

Okai Takanori

Okai is a traditional craftsman accredited by Nara Prefecture. He explains, “When weaving Nara Sarashi, twisted hemp yarn is used in the warp and untwisted hemp yarn in the woof.” While explaining, he operates the weaving loom known as yamatobata. He says, “The unique weaving process gives Nara Sarashi its distinctive sheen, softness, and absorptive properties.” Nowadays, in order to allow users to enjoy the unbleached color, the cloth is only washed when making tea ceremony items.

AUTUMN | August–October

In Nara, the Shosoin Exhibition is closely associated with autumn.

Approximately ten thousand treasures brought to Japan via the Silk Road have been preserved at the Shosoin Treasure House for over 1260 years.

Nara Fude (writing brushes) may have developed from the brush used to paint the eyes of the

Great Buddha, and Nara Sumi (ink) from clods of ink used in copying sutras.

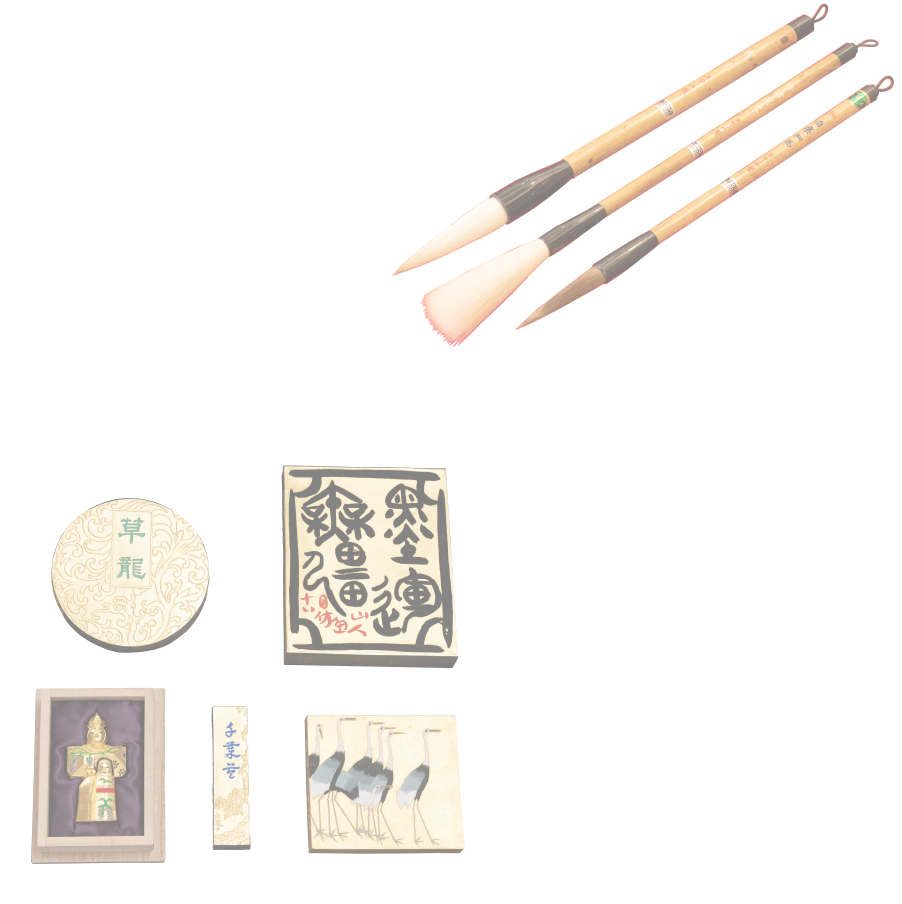

The use of colors and patterns on the treasures stored in the Shosoin Treasure House continue inspiring contemporary Nara-made artifacts.Nara Fude

The roots of Nara Fude writing brushes lie in the Kamimaki Fude, a type of writing brush brought to Japan from Tang Dynasty China by Kukai, the founder of the Shingon sect of Buddhism. In those days, the manufacture of these brushes involved the latest technology. It is said that Kukai had Sakanai Kiyokawa, an artisan in Imai Town, Yamato Province (present-day Nara Prefecture) create a brush for presentation to the Emperor Saga and his Crown Prince.

Descendants of Kiyokawa engaged in manufacturing writing brushes in Imai Town, but later transferred the business to Nara City, a main production area for ink-clods. The plethora of temples located in Nara City created a great demand for ink and writing brushes, resulted in increased development of these items. Later, in the early Meiji Era (1868-1912), artisans mainly created writing brushes known as “Mushin Fude” or “Mizu Fude,” in which hard and soft strands of hair are mixed and stuck together. Thanks to the high-quality writing brushes it makes, Nara is one of Japan’s main brush production centers, along with Hiroshima, Aichi, Sendai and Niigata. The Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry has designated Nara Fude as a traditional craft product.

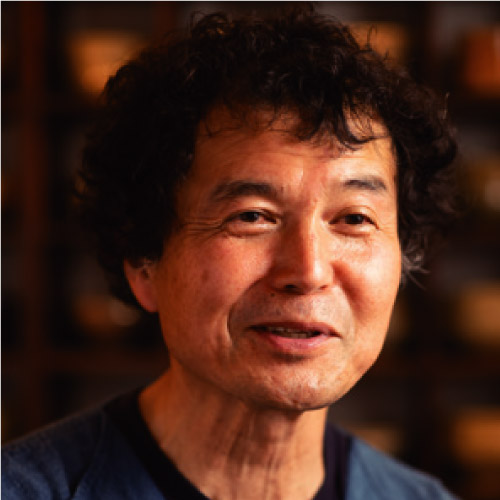

Matsutani Fumio

Matsutani proudly states, “The entire process of creating Nara Fude is carried out manually.” He has been manufacturing writing brushes for over 40 years, and is accredited as a traditional craftsman by Nara Prefecture. While spreading and mixing various types of hair cut into different length depending on the functions they are to fulfill in a brush, Matsutani explains: “Nara Fude uses hair taken from Japanese weasels, goats, deer and racoon dogs.” This process, called nerimaze (kneading), greatly affects the appearance and condition of the brush.

Nara Sumi

In Japan, clods of ink are of two types. These are shoenboku, made of burnt pine resin, and yuenboku, made from the lampblack of sesame, rapeseed or tung oil. Nara Sumi was formerly called “Nanto Yuenboku” (yuenboku made in Nara). The processes of making clods of ink and of producing writing brushes were introduced to Japan by Kukai, who visited Tang Dynasty China as a member of a Japanese envoy mission. Kukai is said to have made ink-clods at the Nitaibo Branch Temple of Kofukuji Temple. Production of shoenboku ink-clods began in Kishu (present Mie Prefecture) and Omi (Shiga Prefecture) toward the end of the Heian Era (794-1185) but ended in the Kamakura Era (1185-1333). In the Azuchi Momoyama Era and afterwards, ink-clods manufactured in Nara became increasingly popular, with many manufacturers established in Nara. Nara Sumi accounts for 90 percent of the market share nationwide and is designated as a traditional craft product by the Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry.

Matsuda Eiji(left) / Nishioka Atsuhito(right)

Nara Sumi is manufactured between October and April, as the glue used to make it spoils quickly in hot weather. Nara Sumi is used not only for calligraphy but also for ink-brush painting. It is often said that “There are seven shades of black.” Nishioka and Matsuda are ink-clod molders. They concur in saying that Nara Sumi is characterized by beauty of appearance. Lampblack, glue solution and fragrances are mixed and kneaded into sumidama, a rice cake-like dough of ink. Experienced artisans mix and knead the sumidama with their hands and feet. This is how glossy Nara Sumi is made. Even the surface rubbed into an inkstone is beautiful.

WINTER | November–January

Winter in Nara is crisp and cold.

However, we feel warm and cozy with reddish-tinted Akahadayaki pottery in hand. Lovely Nara-e (Nara-style illustrations) are often painted on the pottery.

Chic artifacts created in Nara add grace to the Kasuga Wakamiya Onmatsuri, a year-end series of festivals held at Kasuga Taisha Shrine.

Among these are Nara Ittobori sculptures displayed on altars for the Ooshukushosai Festival. The roughly chiseled, flat surfaces of Nara Ningyo (Nara Dolls) are expressive, and attract the eye.

Akahadayaki

The Nishinokyo hills produce high-quality porcelain clay. For this reason, the ceramic industry has flourished in this area since olden times, with a variety of items such as charcoal braziers and other clayware being produced. With the founding of tea-ceremony culture, earthen braziers came into being. In the late 16th and early 17th centuries, Toyotomi Hidenaga, the lord of Yamato Koriyama Castle in Nara, hired potters from Owari Tokoname (present-day Aichi Prefecture) to produce ceramic tea ceremony utensils. Later, Yanagisawa Gyozan became the lord of the castle in the middle of the Edo Era. He hired potters from Kyoto and promoted Akahadayaki pottery as government pottery for Koriyama Domain. After this, skillful potters such as Aoki Mokuto and Okuda Mokuhaku came on the scene. While traditional Akahadayaki works decorated with simple Nara-e (Nara-style illustrations) continue to be valued, nowadays there are many new styles with unique colors or shapes.

Oshio Tadashi

Oshio explains, “Clay used in Akahadayaki contains iron. When glazed and baked, the clay reacts with the iron, creating a warm impression. Okuda Mokuhaku, the founder of Akahadayaki, made it known that he studied pottery all over Japan and thus had the skill to produce works of pottery patterned after them. Indeed, Okuda produced pottery of various styles. This is another feature of Akahadayaki that should be passed down to future generations.” True to his word, Oshio displays pottery of many different styles in his workshop.

Nara Ittobori

Nara Ittobori sculptures are also referred to as Nara Ningyo (Nara Dolls). Their origin is said to lie in the colorful dolls used for Kasuga Wakamiya Onmatsuri, a year-end series of festivals at Kasuga Taisha Shrine held continuously since the end of the Heian Era. At the festivals, the Nara Ittobori dolls are displayed on altars. In addition, dengaku (a ritual dance) performers wear hats adorned with flowers and these dolls. Beginning in the middle of the Edo Era, master-sculptors successively named Okano Shoju (1st to 13th generations) gained repute. Another sculptor, Morikawa Toen, was active at the end of the Edo Era and the beginning of the Meiji Era. Featuring roughly and dynamically chiseled, flat surfaces and rich coloration, Nara Ittobori has come to command attention as artwork. There is also the theory that Nara Ittobori features roughly chiseled surfaces as a way of conveying simplicity and thus purity, the dolls being used for Shinto rituals. Traditionally, Nara Ittobori are modeled on characters from Noh, Kyogen or court dance, as well as deer (in Nara, considered a sacred animal). Nowadays, hina dolls (displayed for the Girl’s Festival in March) and those patterned after Chinese zodiac animals or samurai helmets are popular.

Araki Yoshindo

Araki says, “I always focus on how the flat surfaces of wood can make the dolls attractive.” The animated, gorgeous dolls he creates are very popular, and orders come in from all over the country. In soft but passionate tones, Araki continues, “Nara Ittobori sculptures have a sense of presence. They’re suited for display in modern houses. Items based on particular seasons are especially popular. I want to convey the appeal of traditional Nara Ittobori to many people while pursuing my own style. Ittobori is an excellent sculpture technique. The technology, as well as the historical background in which the technology has developed, is a culture of which Nara should be proud.”

Messages to the Future

Interviews with talented young artisans who maintain the long tradition of Nara craftwork and will pass it along to future generations.

Maeta Hiroyuki

The interview with Maeta was carried out while his work “Minamoto no Yorimasa Vanquishing the Nue” was exhibited at the Nara Crafts Museum (exhibition now closed). A nue is a creepy monster with the face of a monkey, limbs of a tiger and tail of a snake. The nue appears as if it is about to attack the samurai warrior Minamoto no Yoritomo. Yoritomo wears no shoes, only tabi socks, and there is no quiver on his back. Maeta says, “This work represents a famous scene from the war chronicle ‘The Tale of the Heike.’ However, I didn’t follow the rules regarding the costume and weapons of the samurai. What I tried to do was to convey the elusive character of the monster. I became interested in craftmaking when I was a junior high school student, and studied Nara Ittobori at the Nara Crafts Museum. It’s been 16 years since I started my career as a sculptor. I have a lot of ideas I want to represent in my works. Now I’m making a doll modeled after the Noh play character Kasuga Ryujin. The life force of a doll is expressed by its face, but I’m partially hiding the doll’s face with its hair. That way, the solemnity of the doll’s character is enhanced.” Maeta is passionate about expressing his own unique worldview.

Photograph Captions

(Top left) Maeta carefully carving details with a graver

(Top right) Roughly chiseling wood, Maeta forms the approximate shape out of the wood

(Bottom) Maeta’s “Minamoto no Yorimasa Vanquishing the Nue” conveys the tensity of the scene

Profile

Maeta studied Nara Ittobori under Kamihashi Torin, the fifth accredited-sculpturer at Kasuga Taisha Shrine. He completed the three-year training program of the Nara Traditional Craft Successor Training Program, as a member of the program’s inaugural class. His work “Igo Match between Black Demon and White Demon” won first prize in the popular vote at the 1st Nara Traditional Crafts Exhibition. In 2016, Maeta produced a hina doll stand given to Hometown Tax payers.

Yao Satsuki

During Yao’s university days, when she studied Heian-Era inkstone cases, someone suggested that she make a replica of a case for research. When she touched the lacquer for the first time, she suffered an adverse reaction, and gasped for breath. She laughs, “I discovered a new sensation through this experience, and decided to dedicate myself to lacquer art. That may sound strange.” She creates not only traditional tea ceremony items and tableware, but also accessories such as necklaces, pierced earrings and kimono sash fasteners. She explains, “If they like the accessory, users may become interested in the process or the creator.” Yao is working to pass on the tradition to future generations.

Photograph Captions

(Top left) Gold-inlaid lacquerware accessories are very popular

(Bottom left) Carving delicate patterns with a graver

(Bottom right) “Shinobu,” a gold-inlaid lacquerware sake cup

Profile

Yao graduated from the Department of Historical Heritage, Faculty of Art and Design at Kyoto University of Art and Design (Now: Kyoto University of the Arts). She became interested in lacquer art while studying ancient inkstone cases at the university, and pursued her studies at Ishikawa Prefecture Wajima Lacquer Art Technical Research Institute. Later, Yao completed the three-year Nara Traditional Craft Successor Training Program as a member of the program’s fourth class. Yao presents her works at private and group exhibitions.

STORY 2

Nara, the City of Artifacts:

Its 1300-Year-Old History and its Present

Historical Events and Nara Crafts

An overview of transitions among Nara crafts of each genre, and of historical events in Nara and Japan

Nara Era (710-794)

Beautiful artifacts brought to Japan via the Silk Road

During the reign of the Emperor Shomu (Nara Era), various cultural objects were brought to Japan via the Silk Road by Japanese envoys dispatched to Tang China and by foreign delegations to Japan. These objects were instrumental in defining beauty in those days. The treasures stored in the Shosoin Treasure House convey details of this beauty to us.

Modern Nara craftworks derive from these outstanding ancient crafts, in types such as woodwork, mother-of-pearl work and textiles. In addition, prayers and rituals have come down to the present day in the form of religious events, one being the Omizutori Ceremony held at Nigatsudo Hall at Todaiji Temple each March. The ceremony first took place in 752, the year in which the temple’s Great Buddha statue was dedicated, and has continued without interruption for 1270 years.

The bright colors and exotic shapes of the Shosoin treasures remain often-used motifs for Nara crafts today, as do the imitation camellias offered to Buddhist deities at the Omizutori Ceremony.

Heian Era (794-1185)

Transformation into a center of faith for the nobility

After Japan’s capital was transferred from Nara to Kyoto, Nara came to be referred to as Nanto, the Southern Capital. Nara was no longer a political center, but maintained its position as the center of religious faith. Imperial families and the nobilities visited Nara regularly to worship at major temples and shrines, such as Todaiji Temple, Kofukuji Temple and Kasuga Taisha Shrine.

It is believed that, already in the Nara Era, there existed the custom of periodically reconstructing shrine buildings, a practice known as zotai (or, sengu). At important shrines in other parts of the country this custom largely died out, but it has continued without interruption at Kasuga Taisha Shrine down to the present day. Sacred treasures and various other furnishings are also created anew for zotai, playing an important role in assuring ongoing craftsmanship in Nara in crafts such as lacquerware or pottery.

The Kasuga Wakamiya Onmatsuri, a year-end series of festivals held at Kasuga Taisha Shrine, is also adorned by various artifacts. Initiated in 1136 by the Kanpaku (chief adviser to the Emperor) Fujiwara Tadamichi, the festival has continued for nearly 900 years. Wooden dolls displayed on altars and decorated on the hats worn by dengaku (a ritual dance) performers are believed to be the origin of Nara Ittobori sculptures, also referred to as Nara Ningyo (Nara dolls).

Muromachi Era (1336-1573) - Edo Era (1603-1868)

Development of wabichain in Nara

Chanoyu, or the Japanese tea ceremony, is referred to as a “composite art culture.” The tea room and garden around it, the crafts used as utensils, the food served and the flowers displayed are orchestrated as a whole.

Wabicha is a style of tea ceremony regarded as the origin of sado, today’s tea ceremony style. Wabicha was originated by Murata Juko, a tea ceremony master of the mid-Muromachi Era.

Born in Nara, Murata Juko became a monk at Nara’s Shomyoji Temple. His teachings were transmitted to the successive heads of the Matsuya Family (known for compiling the tea ceremony record “Matsuya Kaiki”), Senno Rikyu (a tea ceremony master of the 16th century), and the 16th-century military commander Oda Nobunaga, with these teachings being refined until the present day.

Honoring Nara as chanoyu’s place of origin, a cultural event entitled “Juko Chakai (Juko Tea Party)” has been held annually each February since 2014. In connection with this event, the major sado schools conduct tea ceremonies at temples and shrines around Nara City.

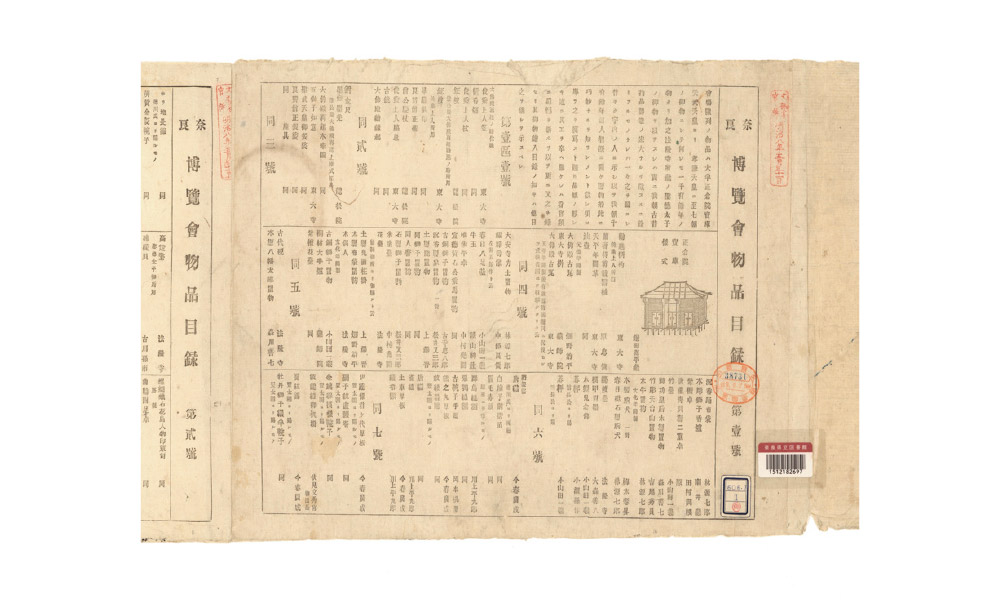

Meiji Era (1868-1912) - Present

The Nara Exhibition–A turning point in the history of Nara crafts

During the Meiji Era, the days of samurai warriors came to an end, giving way to modern times. The government promoted new industries, enabling Japan to catch up with the West. In the early Meiji Era, Nara, where major temples were located, was caught up in a movement to abolish Buddhism aroused by a government-issued ordinance to separate Shinto and Buddhism. However, Nara temples gradually regained power, because the city had coalesced around temples and shrines after the capital was transferred to Kyoto and, accordingly, the locals were exceedingly devout. Traditional crafts, which developed along with religious customs, also overcame the social difficulties and became a focus of attention. The Nara Exhibition, a major event held 15 times between 1875 to 1890, marked a key turning point for Nara crafts. The main venue of the government-promoted event was the cloister of the Great Buddha Hall at Todaiji Temple. At the exhibitions, in addition to Shosoin treasures and secret treasures held by local temples and shrines, craftworks made by skillful artisans were displayed and attracted attention. These craftworks included Nara Ittobori created by Morikawa Toen and Nara Shikki pieces by Yoshida Hoshun. The exhibition is a landmark for the development of those Nara crafts that have been passed down to the present day.